When One of These Shadows Moves (Part One)

An interview with James Baldwin, 1972.

BY TONY WOLK

Intro & Part One | Part Two | Part Three | Part Four

INTRODUCTION

“The acceptance of our present condition is the only form of extremism that discredits us before our children.” —Lorraine Hansberry

IN 1972 I WAS a fairly young professor of English at Portland State University and had been teaching evening freshman-level composition classes (as an overload) for about three years at the PSU Education Center, a small store-front affair which had been the headquarters for the McCoy Plumbing Company. It was situated on Union Avenue across the river from the main campus. (In 1989, the city changed the name of Union Avenue to Martin Luther King, Jr. Avenue—farewell Union Avenue and its celebration of the resolution of the Civil War and the end of slavery.) There were also intros for math and psychology. The goal was to bring the university to the black community. Tuition for the three-credit classes was a mere six dollars per class! Our students were primarily middle-aged black women, though the first term our composition class consisted of three white women. That soon changed. Before long a few of my best students were team-teaching with me. I recall one class with about a dozen students and six of us teaching. Lots of one-on-one opportunities.

Right from the start we departed from the A-F style of grading. Many of our students did not have high school diplomas. That non-grading system has continued on, not just at the Ed Center, but, for me, with all of my classes. My syllabi have a note reading something to the effect that I’m doing my best and I expect you to do your best. Instead of writing a letter grade on a paper, I respond in detail in the margins, often enough scrolling their papers into my vintage Groma typewriter—much better than obliging them to puzzle out my handwriting. Besides, the typewriter allows me more fluency.

I’ll mention just one fellow teacher, Mel Toran, a black man about my age. Mel was amazing, and after his first term, he became one of our fellow teachers. Mel went on to become the first black student to graduate from the University of Oregon Law School; from there he returned to his home town, Erie, Pennsylvania, where he worked with Legal Aid until his death.

Before long I was also team-teaching a year-long Black Literature course, my partner, Lloyd Baker, a black T.A. from the English Department. Both of us had to get up to speed. It was about then that there was a National Council of Teachers of English meeting in Portland (a sub-group called the Conference on English Education). One session on black writers was held at the Ed Center, its three presenters all white women. When they were done, the women in the audience, several from black universities in the South (only one name do I recall, Vivian Davis) began to rattle off names and titles I didn’t know, such as Ronald Fair’s Many Thousand Gone, William Melvin Kelley’s Dem, John Oliver Killens’ And Then We Heard the Thunder, Claude McKay’s A Long Way from Home. Furiously I jotted down names, then began haunting used bookstores for the books.

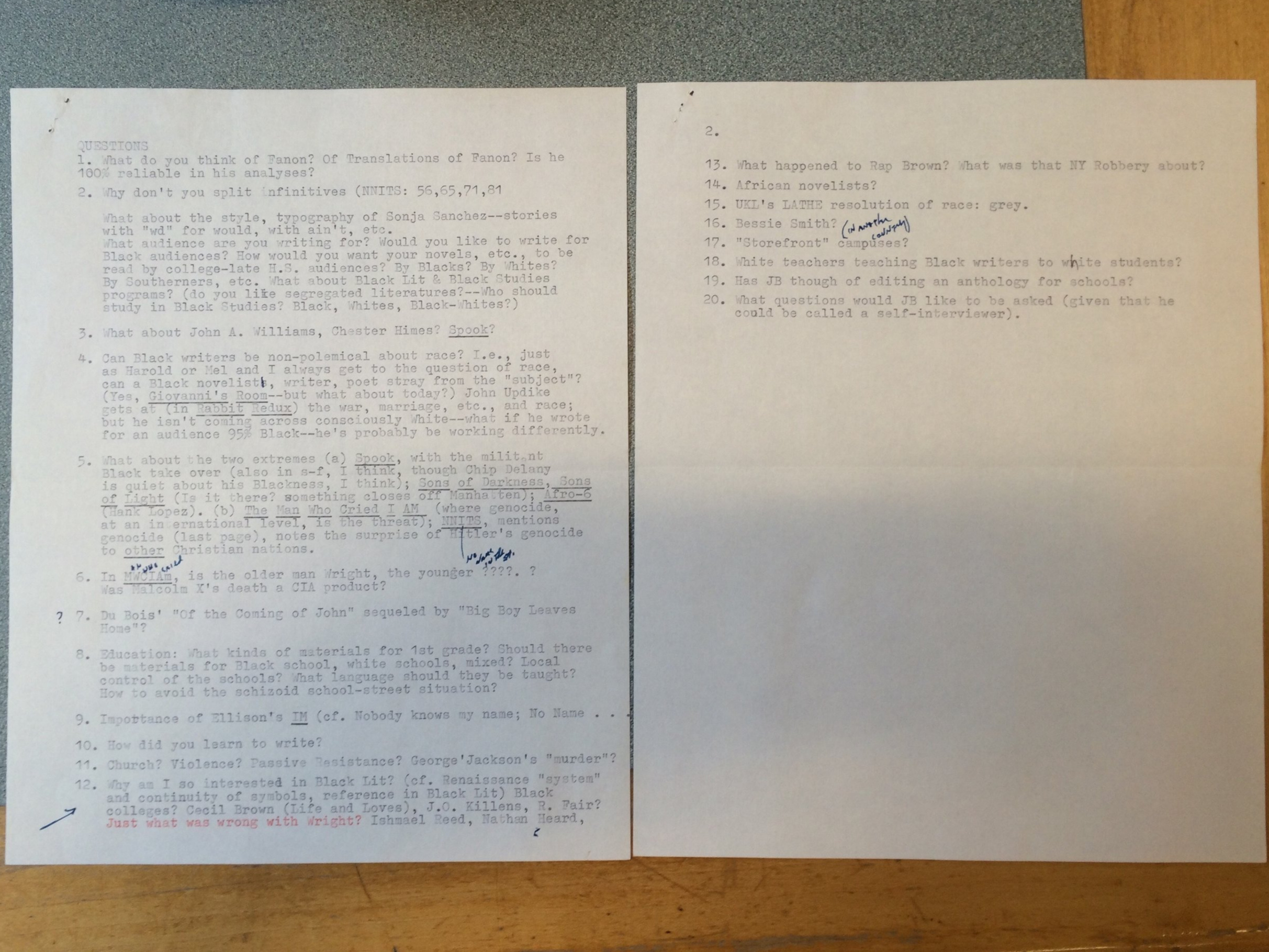

Two pages of questions, recently rediscovered, that Wolk brought to his interview with Baldwin.

Come the fall of 1971 I had earned my first sabbatical (the number now is seven) and was living in London with my family. I was reading Richard Wright, Chester Himes, Sam Greenlee, Ishmael Reed, Dick Gregory, H. Rap Brown, Bobby Seale, Franz Fanon, and on and on. I know for sure what I was reading, given that beginning in 1954, my sophomore year at Northwestern, I began to keep in a small notebook a list of every book I read—I’m still doing it, now on my computer, given that the little brown book ran out of pages—I even had a graph for how many books/year I had read. The number now is getting close to nine thousand, though exactly what a “book” is varies. What my little book tells me about the spring of 1972 is that I had read (or reread) four Baldwin books in a row: Go Tell It on the Mountain, The Fire Next Time, Nobody Knows My Name, and Notes of a Native Son.

At which point my wife (who was a journalist) got word that James Baldwin would soon be in London for a press conference, thanks to his publisher Michael Joseph, to launch his newest book, No Name in the Street. There would also be the possibility of personal interviews—more detail to be supplied at the event. I compiled a list of twenty questions to ask. (I had forgotten about the list, and was surprised a few days ago when two folded-over pages slipped out of one of my hardback Baldwin books.) At the end of Baldwin’s presentation came the announcement that Mr. Baldwin would be glad to do a few personal interviews in his hotel room at the Britannia Hotel. What we were waiting for! We had a couple of hours before our scheduled interview, enough time for lunch. Then at one p.m. there we were, knocking on the door of Room 515. (Strangely, we were the only ones requesting an interview!)

By now you’re probably wondering why it’s taken me nearly fifty years to share the interview with the public. I have no solid answer. I write articles about Shakespeare, language attitudes, Philip K. Dick. I’ve written many novels, three of which were published by Ooligan Press, housed one floor down from my office, as well as a short story collection, The Parable of You, thanks to Dan DeWeese and his Propeller Books. I’ve read numerous papers at conferences, done readings by the dozens for my several books. I’ve also team-taught science-fiction writing three times with Ursula K. Le Guin (which is what brought me home to my early love of writing poems and stories). Since Ursula’s death a year and a half ago, I’ve written, by request, several articles about her work and life (which I deliberately did not do while she was alive).

It’s not that I had forgotten about the Baldwin interview. I knew I was sitting on a treasure, that I should lift the lid and let it see the light of day. But should isn’t would. Maybe it’s my age, eighty-four, that and the sabbatical that makes a difference, and having the freedom to read. About three years earlier I had read Baldwin’s non-fiction books, the ones on my shelf. And then, thinking to give fiction its turn, I read Go Tell It on the Mountain and Another Country. When I got to If Beale Street Could Talk I was blown away, especially by Baldwin’s handling of point of view. Which is when I dug out the Baldwin folder and was amazed as I reread my transcription.

What happened next is circumstantial, like a match to kindling. A former Portland State University graduate student was fired from her job working with unaccompanied immigrants at a long-term group home in Portland after emailing everyone on staff (and also posting the email on Facebook and publishing it on Propeller) with her concerns about the ways in which they were treating and monitoring the children. I responded, one of many responses, by quoting Baldwin’s notion of what a “liberal” was from the interview, which was powerful, even electrifying. (Compare it to this passage from Another Country—it’s Ida being furious with Vivaldo: “Here we go again! I’ve been living in this house for over a month and you still think it would be a big joke to take me home to your mother! Goddammit, you think she’s a better woman than I am, you big, white, liberal arsehole?”)

At which point enter Dan DeWeese once more, saying he’d like to reprint not just the quote from Baldwin, but whatever I had, as well as some or all of the audio. The result was that within two days I’d completed the transcription, realizing as I went along that many readers wouldn’t recognize many of the names (which I discovered was true). For instance, H. Rap Brown. I reread Die Nigger Die! and was blown away by it, then wondered what came next and if he was still alive. What I discovered both infuriated me and well nigh broke my heart. No quick note there, nor after reading Angela Davis’s Autobiography, having stumbled upon it as I was part-way along Baldwin’s “History Is a Weapon: An Open Letter to My Sister, Angela Y. Davis,” dated November 19, 1970, and printed in the New York Review of Books. I then read with a fresh eye George Jackson’s Soledad Brother, and near the end, his five letters to Angela Davis.

Baldwin’s No Name in the Street begins with an epigraph from the book of Job: 18.17-18: His remembrance shall perish from the earth, and he shall have no name in the street: he shall be driven from light into darkness and chased out of the world. What came to my mind was Cain, but that’s from Genesis. A day later I opened my Geneva Bible, read the two lines, then read both chapters. I urge you to follow in my belated footsteps to give the one sentence (and the book’s title) its full resonance.

A book begins, a book ends. I suppose the epigraph can count as a prologue, one that the reader is obliged to supply. The book’s epilogue has a title: “WHO HAS BELIEVED OUR REPORT?” It sounds like a challenge, and of course is just that. Its opening two sentences reflect that challenge: “This book has been much delayed by trials, assassinations, funerals, and despair. Nor is the American crisis, which is part of a global, historical crisis, likely to resolve itself soon.” In effect, You’ve read my book—now it’s your turn!

The epilogue ends with this short paragraph:

Angela Davis is still in danger. George Jackson has joined his beloved baby brother, Jon, in the royal fellowship of death. And one may say that Mrs. Georgia Jackson and the alleged mother of God have, at last, found something in common. Now, it is the virgin, the alabaster Mary, who must embrace the despised black mother whose children are also the issue of the Holy Ghost.

Reading these last words, I’m struck by the resonance of the word “history” in Baldwin’s “Open Letter” to Angela Davis. And that Baldwin signs off on the letter as “Brother James.”

One last note: What was it like being in a room for a couple of hours with James Baldwin (I want to say “Brother James”)? Was it as easy-going as it seems with the back-and-forth of the interview? Electrifying? Yes. And his openness, yes. And his shining face. His smile. His piercing eyes. The depth of his voice and the clarity of thought. Yes. You could only walk away from it loving the man. A once-in-a-lifetime experience.

A Few Recommended Readings (as though the others are to be avoided!)

No Name in the Street: which had just been published in 1972 and was the occasion for the interview.

Going to Meet the Man [Stories] (Vintage, 1995) [First published, 1965]. Includes, “Sonny’s Blues.”

James Baldwin: The Cross of Redemption: Uncollected Writings (ed. Randall Kenan [Vintage, 2010]). Includes about sixty vital and powerful essays, one of which is “The Uses of the Blues” (Playboy, 1964), which bookends with “Sonny’s Blues,” and ends with these lines from Bessie Smith:

Good mornin’, blues.

Blues, how do you do?

I’m doin’ all right.

Good mornin’.

How are you?

Be sure then, to listen to some of the renditions of “Good Mornin’, Blues.”I Am Not Your Negro (Vintage, 2017, from texts by James Baldwin, compiled by Raoul Peck, director of the film I Am Not Your Negro)

James Baldwin: A Biography by David Leeming (Alfred Knopf, 1994).Leeming was a long-time friend and associate of Baldwin.

INTERVIEW WITH JAMES BALDWIN

April 17, 1972

[The recording begins with a conversation in progress about an obnoxious questioner at Baldwin’s press conference. Present were Baldwin; Baldwin’s agent, Tria French; Tony Wolk; and journalist Susan Stanley, Wolk’s wife at the time. The audio, originally recorded on reel-to-reel tape and later transferred to compact disc, has been digitally restored by Lucas Bernhardt. The process involved diminishing tape hiss, background noise, and other audio artifacts from the recording, as well as boosting the voices of those present. What is presented is the entire original recording, unedited.

Links within the transcript take readers to newly-written notes by Wolk, providing his sense of background and context for the various writers he and Baldwin discuss.]

Susan Stanley: It was one of those things where they’re asking questions, but they really aren’t asking questions, they’re making a statement.

James Baldwin: No, they’re not, that’s right, they’re sort of almost putting you on. You can’t take the question seriously.

Stanley: Well, I love the way that you handled the business about democracy as, you know, the worst form of government except for everything that’s been invented before, which is taken from a line from a television program anyway.

Tony Wolk: “Slattery’s People.”

Baldwin: That’s wild.

Stanley: It was an American television program years ago, but you handled it absolutely seriously. You said, “Well now, I don’t know that I really agree with that.” And he was just doing it for a laugh, and I said, “That’s just beautiful.”

Wolk: He wasn’t doing it for a laugh.

Baldwin: I couldn’t tell whether he was serious or not.

Wolk: I think he was serious. I was wondering afterwards how a man who must have some education could sound so stupid.

Baldwin: Yeah, well, that’s what throws you, you know. That’s why I thought maybe he was putting me on.

Wolk: I don’t think so. I think he was defending everything that he had lived with all his life.

Baldwin: He really meant that nonsense about an ideological crusade?

Stanley: Oh, yeah. He was talking about, sort of, professional doom-watchers or something like this, you know, and all I could say was, You don’t know, you know, you don’t know what it is, I mean, even I, being what I am, know more of what it is than he does, and how can he say everything is really hunky-dory, you know?

Baldwin: Yeah.

Stanley: He probably hasn’t been there.

Baldwin: Well, obviously he hasn’t been there. But I don’t know where these people live. I don’t know what they see when they walk around the streets or what they read when they read the newspapers. It’s irritating to be blamed for something you’re observing. I’m not inventing it. Do you want anything like tea or coffee or…

Wolk: I don’t—

Baldwin: —or beer?

Wolk: Or beer?

Baldwin: You do? [Laughter]

Stanley: Doesn’t that sound good at this hour of the day? You know, after we left that, I had two little things of champagne and it was like four hours afterward, I was still like this…

Baldwin: You want a beer?

Stanley: I’d love a beer.

Tria French: I’ll have a tomato juice.

Baldwin: [dialing room service] Hello, this is room five-fifteen. Can we have three beers and one tomato juice, please? Cold beer, yeah. No, three beers. Three. And one tomato juice. Five-one-five. Thank you.

Stanley: We don’t speak the same language.

Baldwin: No, we don’t.

Wolk: I can’t imagine what the other end of the conversation was like.

Baldwin: They wanted to know how many glasses I wanted for the beers. [Laughs] I said three beers, didn’t I? And he said how many glasses?

Stanley: Oh, I’ll bet he thought one person was going to sit up here and drink…

Wolk: I’ve been wondering, in your writing, what audience you’re writing for. Are you writing for, say…

Baldwin: Are you speaking of one thing?

Wolk: Well, obviously a fair amount of your writing is, I guess you’d say polemical, although it’s autobiographical. To make the question more specific—

Baldwin: Watch your glasses.

Wolk: —are you writing for, say, the kind of audience that would have been to college, or an audience which is predominantly white or black? Or is that something that you think of, or that you don’t think of as you’re writing a book?

Baldwin: Well, the truth is that you don’t feel it as you write the book. I think you begin to be aware of your audience after the fact. And it would seem that a lot of my audience are young people. If I’m writing for anybody, it’s probably for young people.

Wolk: As a college teacher, another part of the question is, how would you want your books read?

Baldwin: How do you mean?

Wolk: Would you want them read in literature classes? What kinds of questions would you want people to be asking about your books, or what would you like them to be seeing in your books?

Baldwin: Well, that’s not up to me, is it? You can’t foresee the questions that a book will raise in somebody else’s mind.

Wolk: I’ve never taught any of your books, so it’s not a question with a book in mind.

Baldwin: No, I know, I know it isn’t. But I don’t know how to answer it, because on one level I’m not much interested in literature.

Wolk: You’re not much interested in literature?

Baldwin: I’m not much interested in talking about it.

Wolk: I’m not, either. I shouldn’t say that.

Baldwin: I don’t know. I suppose I just want—I don’t know what a book does. I suppose I want people to ask questions, but I don’t know what kind of questions they’re going to ask.

Wolk: I find out the best way to…as a teacher, it’s disastrous for me to lead the kind of questions, and ask the questions of the students.

Baldwin: Yeah. Let them do it.

Wolk: Sometimes they don’t have any questions, then you just go on to something else. I’ve been learning that lately.

Baldwin: You can’t pry it out of them. They have their own timing.

Wolk: As a teacher, would you already know before you ever opened a book what questions to ask about it?

Baldwin: I think that’s a great thing you’re doing. They obviously react against that. Be as blank as possible.

Wolk: I’d be interested in what you think about specific writers. For about a year and a half I’ve been reading a fair number of books by blacks. For instance, John A. Williams.

Baldwin: I’ve read him, yeah. It’s a little difficult for me to discuss other writers.

Wolk: I realize that. Maybe a specific question about The Man Who Cried I Am, which I don’t know if you’ve read that.

Baldwin: I haven’t read it, so I can’t really…

Wolk: The reason I ask about that one is it’s one which deals with the apparent international plot—

Baldwin: Yeah, I know.

Wolk: —of genocide. And the elder character sounds like the dean of American black writers. For some reason, I figured it must be Richard Wright, or something like that, if you can make a jump like that.

Baldwin: Well, I haven’t read the book deliberately because…for lots of reasons. People tell me a lot of things about it. And it was simpler for me not to read it, you know. I’ll read it sometime when I’m ready, you know, away someplace. And no one will ask me about it. I like one of his books very much, it’s called Sissie.

Wolk: As a matter of fact, I taught that book last year.

Baldwin: That’s quite a book, I think. And I like Night Song, parts of it, very much. And Sissie I like very much indeed.

Wolk: Does John A. Williams live in—

Baldwin: Lives in New York. At least that’s where I’ve seen him.

Wolk: I read that he had done an interview with Chester Himes, which I didn’t get to read, which was very interesting, well done.

Baldwin: Chester is quite somebody.

Wolk: I read about half a dozen of his books, which are set with the two policemen, Grave Digger and... I noticed in one place you mentioned something about Himes that he was the only black writer that you’ve ever encountered who didn’t deal with the subject of violence so much, but dealt with the [inaudible]

Baldwin: Something like that, yeah, yeah. I’ll tell you how I got involved.

[Here the tape had to be changed, and a section of the conversation is missing during which Baldwin apparently brought up Chester Himes’ first novel, If He Hollers Let Him Go.]

Baldwin: I forget.

Wolk: I think that must be one I haven’t read.

Baldwin: It’s his first novel. It’s a very good novel.

Wolk: It’s probably out of print.

Baldwin: Probably out of print, yeah.

Stanley: I guess by the title—

Baldwin: They made a very bad movie with that title, but it had nothing to do with Chester’s book.

Stanley: Whatever became of the Malcolm X thing?

Baldwin: Uh…Thea?

Thea: Oh, it’s still—

Baldwin: It’s about to be published and it will now be produced. On my terms, that is.

Wolk: Did you work with Alex Haley at all? Is he involved at all?

Baldwin: Not in the movie, no. Alex is a very good friend of mine but he was busy doing—you know, he’d done the book. He didn’t want to have anything to do with it. And quite rightly. He was doing another book.

Wolk: Is the other book that he’s doing the one about his ancestors?

Baldwin: That’s right, yeah, that’s Before This Anger, which should be out very soon. I saw some of it. It looks very, very, you know, very exciting.

Wolk: I have a tape of a speech that he gave at Portland State, where I teach. It was given around three years ago, or four years ago, and he said the book would be out in a couple of months.

Baldwin: Yeah, but since then he’s been on so many voyages, you know. He ended up someplace in Holland or England, I forget. Wherever the boat sailed from.

Wolk: He had already done that when he spoke. He had already completed that part of it.

Baldwin: Then I don’t know what happened. I haven’t seen Alex for a little over a year. I saw him in San Francisco. At that time he took a boat someplace. To get away from San Francisco.

Intro & Part One | Part Two | Part Three | Part Four