The Northport Stories: Life on the Edge

The coastal visions of Sheila Evans.

BY DAN DEWEESE

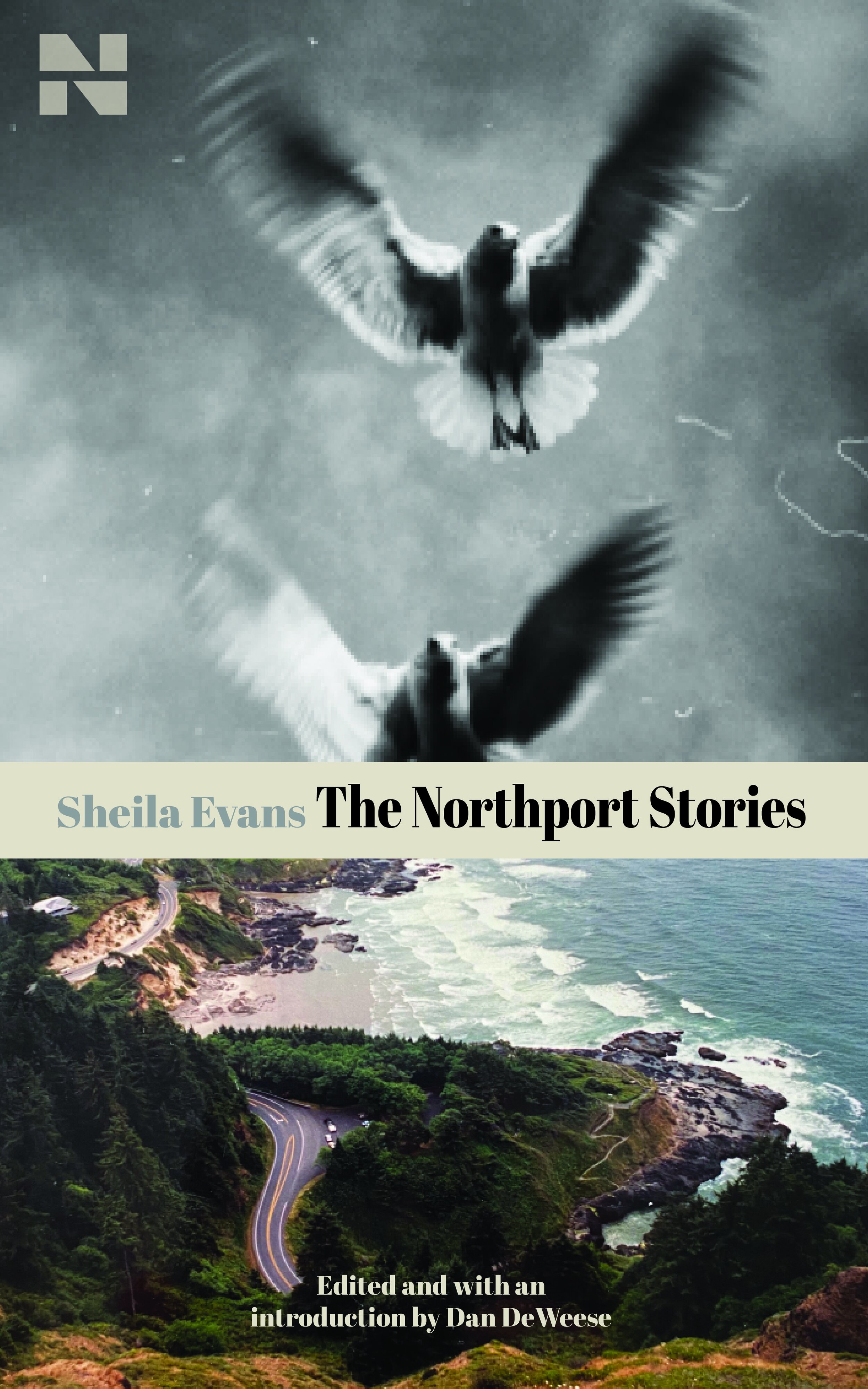

In 2021, while looking over lists of past Oregon Book Award finalists, I came across a title and author I hadn’t heard of: Northport: Stories of the Coast by Sheila Evans. The book had been a finalist in 1999, but Evans’ name did not appear again in subsequent years, she did not seem to have a website, and the only editions of her books I could find for sale were used or electronic. This is not particularly unusual—small presses come into and slip out of existence all the time, and even the largest publishers allow the majority of their backlist to fall out of print. When I found a copy of Northport, though, I discovered it had been published by the “Central Oregon Coast Writers’ Co-op,” with a post office box address in Yachats, Oregon. It did not take much more research to discover that the Central Oregon Coast Writers’ Co-op was essentially Evans. She had worked on her stories for a number of years, and in 1998 she used what looks like an already slightly behind the times word processing program to format the stories and have them printed as a perfect-bound book. She used a photo of Yachats by her friend Sally Grant Carr for the cover.

What I found inside the book was surprising. There are no beautiful descriptions of the Oregon Coast (despite the fact that the Oregon Coast is famous for its beauty), and Evans is likewise unsentimental about the professional and romantic choices that have landed her characters in her fictional coast town. Her narrators—mostly women—are working on second or third marriages, nursing wounds from the past while negotiating the present, and fairly at sea about their future. They are as likely to double down on their delusions as they are to discover some kind of emotional truth.

There is also, humming in the background like the power lines that web the streets of the town, a constant tension between isolated Northport and the bigger world east of the Coast Range. Though characters have business (and children, and pasts) in the inland Oregon cities of Portland, Eugene, and Bend, the tension isn’t just spatial, but temporal, as well. The smaller towns of Oregon are depicted as places the waves of American culture and fashion reach last. As one of Evans’ narrators puts it as she sorts through memories of a broken marriage and failed affair:

It was 1975 and I was caught up in the sixties madness. It had hit us late out there in Bend. We never suffered big city horrors like draft-card burnings or peace marches or sit-ins in our schools; we were a decade behind any new ideas—they sifted in like spores from the Valley or down from the Gorge—but when they hit us, or at least when they hit me, I was hammered.

Though the stories present as tales of interpersonal conflict, the characters’ differing relationships to contemporary American culture, or at least what they’ve heard about it, provide those conflicts with extra spin. Some of the characters—mostly the women—are intrigued by the social changes they hear happening in the cities, and they daydream about wearing “outrageous hats and paisley scarves and big, clunky jewelry.” They do not always act on these dreams, but the dreams inform their feelings about their current circumstances.

““In a collection of stories that could certainly be filed under the literary category of ‘unsparing,’ one can see Evans also likes to have fun.””

Other characters—mostly the men—are in Northport to escape or avoid these exact changes and challenges. If you are looking for dynamic men with noble goals, you will not find them in this book. In one particularly devilish story, a man named Dick explains how his desire to have a relaxing dinner party with his wife and another couple is in various ways frustrated. He reveals, in the telling, the role played by his own casual racism and misogyny. Evans seeds the story with double entendres that suggest the real source of the man’s frustrations is neither immigrants nor his wife, but something more personal: he admires the “loops standing erect” on his immaculate shag rug—“Dick was not sorry he’d jerked it up” and taken it with him from a previous house. In a collection of stories that could certainly be filed under the literary category of “unsparing,” one can see Evans also likes to have fun.

She also combines the two—psychological truth and language games—by skillfully exploiting the potential of unreliable narrators. Her characters often protest slightly too much. This is not the broad unreliable narration of a criminal trying to pass as a regular guy, but the subtler slippage of characters who relate how they are wiser now that they are on their second or third marriage, while the reader can see them drifting directly toward their past patterns and arguments.

One senses Evans was also happy to make herself the target. It is foolish to try to find an author in her stories—Evans is certainly everywhere in this book—but a story late in the collection, in which a woman becomes frightened by how much she gossips about her neighbors in order to impress a new, younger friend, is tantalizing in the meta-textual reading it teases:

In short, I told her the village gossip. The question is, why? Me, so secretive I don’t even like people seeing what I’ve got in my cart up at the Suprette, why did I go out on a limb like that? I don’t know, except I just lost control with her listening so intently, so earnestly. I sang like a canary, then dragged myself home, exhausted.

Exhausted. It is a recurring condition in these stories—rarely physical, usually mental or emotional. And it is often as rendered here: the new friend is not who is exhausting this woman. What’s exhausting is the battle the narrator wages between the need to let go, to tell it all, and the need to preserve a degree of self-protection. She maintains her balance by making sure the tug of war between her competing inclinations ends in a stalemate. It’s tough.

The cover of this book states that I edited it, and I imagine some readers will wonder what kind of alterations this indicates. By the time I read Northport and decided to track down its author, Sheila had been in memory care in Roseburg, Oregon, for a number of years, and a conversation about stories she wrote in the 1990s wasn’t possible. I spoke to her daughter, Paula, who, along with Paula’s husband, Joe, was helpful in providing memories of Sheila’s years in Yachats.

Paula described the sensation, well-known to families of fiction writers, of seeing familiar characters and situations in her mother’s stories, but with different names and details. Paula also recalled her mother mentioning driving to Portland one day to talk to a printer about printing a book (Sheila’s own, we assume), and on other occasions mentioning meeting with her writing group. Paula and Joe both agreed that although her mother found peers and a printer, one of the things she did not have access to was the help of any kind of editorial team. If Evans had lived closer to the centers of the publishing industry, she would have been lauded and well-known. But would she have had the chance to capture so clearly these unsparing stories of life on the edge?

Sheila didn’t need much help—the editing I have done is minor, traditional, and mostly falls under the category of moments in which Evans had already achieved the effect she was after and additional language was unnecessary. I’m speaking here of an adverb that appears when a character’s tone or attitude is already clear, or a second metaphor that appears even though the first was more exact. I’ve removed various moments like these when I felt additional language diminished an effect. Similarly, Evans had a formidable ability to land her stories on a solid, resonant ending. Occasionally, though, she added a few more sentences to explain the resonance. In a few cases I’ve cut or transposed some lines in order to let the story end on the landing. Some readers may feel altering a final line is a step too far, but also: endings are hard, and editors often see them when the writer cannot.

All of this is to say: this is a book by Sheila Evans. I have approached the book as an admirer who feels Evans found herself working in a place and time others were not, and with skill, acuity, and humor, she captured it. Northport was her town.

Dan DeWeese is the publisher and managing editor of Propeller Books. His novel You Don’t Love This Man (2011) was a finalist for the Ken Kesey Award for Fiction and a winner of Late Night Library’s Debut-litzer Prize. Disorder (2012), a story collection, was the inaugural title of the Oregon Book Club, and his novel Gielgud (2018) was a small-press bestseller. His fiction has appeared in publications including Tin House, New England Review, Washington Square, and The Normal School, and his essays and criticism have appeared in publications including Oregon Humanities, Boneshaker, Matter, and Democracy in Education. He lives in Portland, Oregon.