The Stories We Tell About Guantánamo

Sarah Mirk gathers a collection of voices and images from the notorious prison.

BY JOSHUA JAMES AMBERSON

EVENT: On Tuesday, September 8th at 6pm, Powell’s Books Presents Sarah Mirk with Omar El Akkad, Kane Lynch, & Hazel Newlevant.

PORTLAND JOURNALIST, comic artist, and zine-maker Sarah Mirk is a wellspring of creative energy and journalistic depth. Over the past decade, she’s served as an editor and writer for the feminist magazine Bitch and the political comics site The Nib, published hundreds of zines, a series of comics on Oregon history, a relationship self-help book, and a queer sci-fi graphic novel. This year alone, she’s done comics on grocery workers in the pandemic for NPR, Pride comics for The New Yorker, interviewed queer Portlanders about the parallels between COVID-19 and the early days of the HIV epidemic for The Portland Mercury, and self-published the book Year of Zines, to name just a few.

Guantánamo Voices: True Accounts from the World’s Most Infamous Prison, out this week from Abrams, is perhaps her most impressive work yet: a collaborative, in-depth illustrated oral history of the U.S.’s Guantánamo Bay detention camp. Documenting the prison’s history from the beginning of the so-called “War on Terror,” to its time making headlines for the shocking use of torture, to its current state nearly two decades later, in which remaining prisoners (or, in the language of Guantánamo, detainees)—many having no charges against them, and some even cleared for release—sit with no promise, or much immediate hope, of release.

Each chapter in the book is built from an interview with a single subject and combines their words with accompanying context and historical information. The interview subjects include former prisoners, former government officials, former military officers, nonprofit directors, attorneys for Guantánamo prisoners, human rights lawyers, and the current media director at Guantánamo. Incredibly, Mirk turns a complex and often devastating history with overlapping narratives and timelines into an easy-to-follow, page-turning story.

I talked to Mirk by phone two days before the book’s release, while she was trying to return home from a camping trip on Whidbey Island in Washington State, her ferry canceled due to heavy fog.

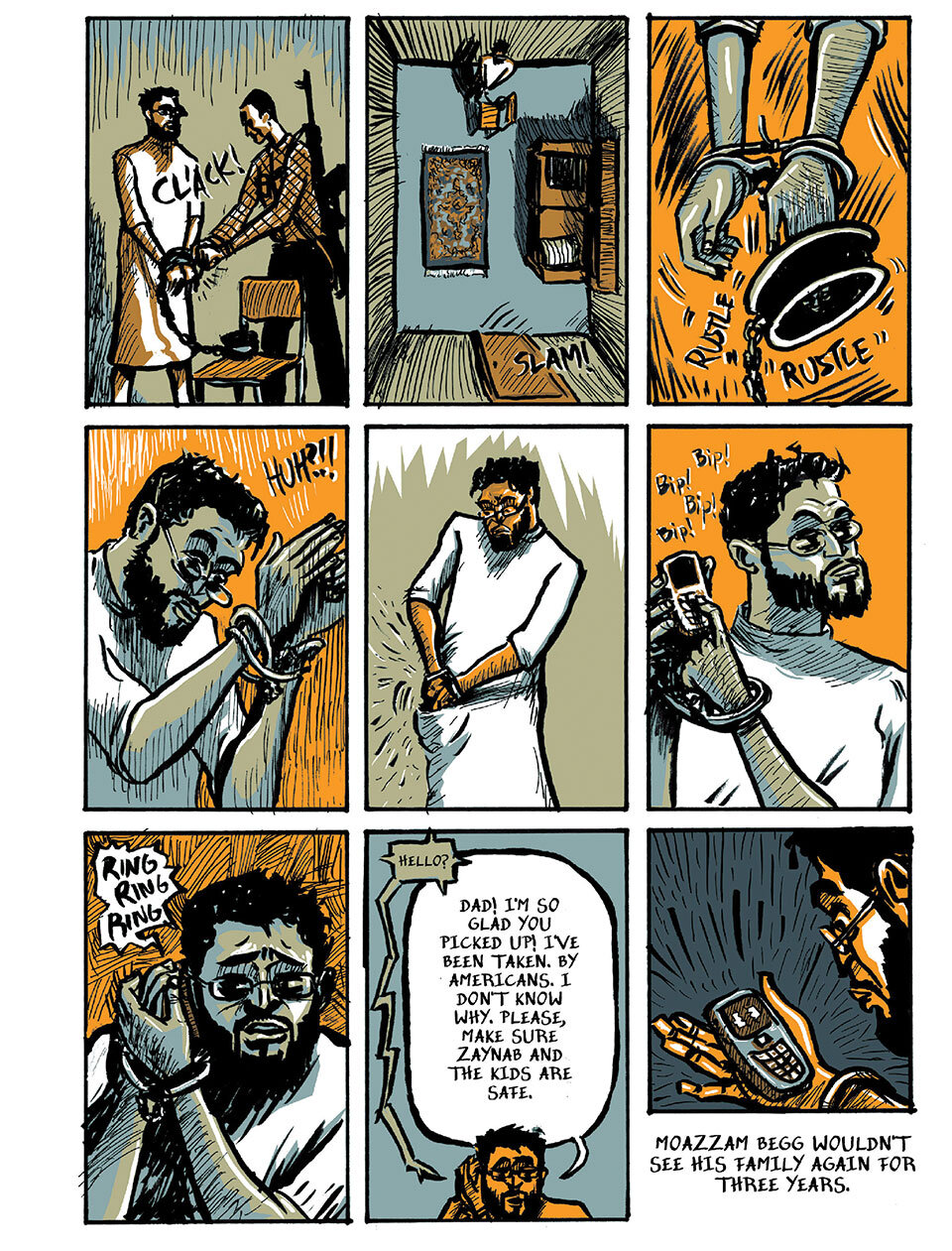

Above, a page from Guantánamo Voices: the story of Moazzam Begg, illustrated by Omar Khouri.

Joshua James Amberson: We get a little bit at the beginning of the book about how your interest in the detention center began—a chance encounter with a Guantánamo veteran a dozen years ago led to you talking to other people who had spent time at Guantánamo—but I’m curious when this turned into a book project for you?

Sarah Mirk: I traveled around England with [Guantánamo veteran] Chris Arendt and former prisoners [in 2009], and I thought I should make something big about it. Like, a big article. But I just didn’t have the skills yet. And I also didn’t know how to tell that story. It just seemed super overwhelming. Then I did a comic for Symbolia Magazine—which is now defunct, but the comic is republished on Narratively and PEN America—with a veteran named Laura Sandow. We made a comic about her story, and after that I was like, “Oh wow, this comic turned out really well. I’d love to talk to more and more people and do some sort of collection of stories of people who have spent time at Guantánamo in different capacities.” So it was after this, about three years ago, that I started thinking about it as a book.

Amberson: Did you always know it would be an illustrated book?

Mirk: Yeah, I was thinking of it as a comic from the very beginning. When I was hanging out with Chris and the former prisoners, I was doing a lot of sketching and made those into zines about Guantánamo—which were really not very good, because I didn’t know what I was doing. But I was thinking about using comics to tell the story because I think that really helps, as a medium, build empathy between the reader and the subjects of the stories. And it also just helps make this place feel real.

Amberson: The book has so many moving parts—nine separate long-form oral history subjects, a dozen different comic artists, so many timelines and narratives and facts to check—how did you manage it all?

Mirk: Yeah, this book was really stressful to make. [Laughs.] I started by reading every other book about Guantánamo. I just went to the library and went to the bookstore and got every book I could find, and from there, found the people I wanted to talk to—those who I thought were most interesting and had different perspectives.

I really feel like I spent the last ten years building the skills I needed to do this very difficult project. Because I’d written books before, I knew how to manage a book project. Because I’d written nonfiction comics before, I knew how to approach writing a nonfiction comic. Because I’d worked on very collaborative projects with artists, I knew what sort of details I needed to manage with those artists. And I’d also done interviews about very difficult subjects before.

So, when I signed the contract to do this book, I initially felt like “What have I done signing up for this? Why did I pitch this? This is impossible.” And then the more I thought it through, I realized that actually I’m one of the few people who has the skill set to pull this off. I’ve spent the past decade developing what I needed to tell these stories.

Amberson: Were the artists all people whose work you knew going in, or did you search out some artists specifically for this project?

Mirk: They’re all artists who have worked for The Nib, so I knew them through being an editor there. I wanted to get artists who had experience doing nonfiction comics, and artists who had the style I thought was appropriate for the subject matter—not too cartoony, not too cutesy, but those who could do something more somber and had the experience of what it’s like to draw comics based on reality. They were almost all people whose work I had edited in the past. There were a few I hadn’t worked with before, but who had made work for The Nib that I loved.

“Guantánamo has just persisted. It’s a huge machine that’s been set in motion, and the path forward is not clear.”

Amberson: Your interview subjects are coming from such different walks of life, and such different relationships to the prison, that I feel as if there must have been some surreal moments as an interviewer. Like, interviewing a former prisoner perhaps soon after interviewing a former counterintelligence chief or the chief prosecutor for the Guantánamo Bay Military Commissions. Did you ever feel any dissonance in the process?

Mirk: I think surreal is the key word with Guantánamo. Everything about it feels surreal, everything about it feels strange. So there are a lot of moments that are surprising. I think for me the most surprising thing is how the people who are working on behalf of prisoners as lawyers—or Mark Fallon, the former NCIS [Naval Criminal Investigative Service] officer—keep working on this issue with no end in sight. Guantánamo has just persisted. It’s a huge machine that’s been set in motion, and the path forward is not clear. What I was always struck by was how people just continue working for what they feel is right and try to do the best they can to seek justice in a very unjust system that shows no sign of changing.

When I’m doing an interview with somebody, I have to be focused on what I’m going to use it for. For comics, you need to talk to them about the visual elements. You have to be like, “What street were you on? What were you wearing? What kind of food were you eating?” Those kinds of detail questions can feel like they’re really missing the point when someone is talking about a big emotional situation. It was tough trying to get the details about these experiences when the experiences were usually pretty terrible.

Amberson: Like, it feels insensitive to ask the detail questions?

Mirk: Yeah. So as much as possible I tried to get material from other interviews that the subjects had done, or books they had written. So I didn’t have to ask detail questions about torture, for example, because they had already written about those experiences. I never want to put somebody on the spot to feel like they have to talk about a traumatic situation. I feel like my job as the interviewer is to do as much research as possible, so I know the questions I don’t have to ask—because I already have that material—and what questions I do need to ask, because they haven’t discussed it elsewhere, or I read a vague description of something that happened and I want to know more about it.

“Would you be one of the people who keeps their heads down and works for six months, gets paid, leaves, and then tries to forget about it? Or would you be someone like Matt Diaz, who tries to undermine the system to do what you think is constitutionally and morally correct and then pay a steep price for it?”

Amberson: I was also struck by how you approached some of the subjects that perhaps had a different worldview than you, like the commander who was serving as the media director when you went to Guantánamo—you did point out the contradictions in his views, but you also seemed curious about what he thought and, at least for the sake of your time together, was someone you got along with. Were people or situations like that difficult to handle on the page?

Mirk: When I was at Guantánamo, I wasn’t sure of my role there. It was definitely as a witness, and as a journalist who was documenting, but for me it really felt like I was on dark ground. I was at a place where terrible things had happened. And being friendly and jokey with people just felt kind of wrong to me. But then, for the people who are working there, it’s a regular day. They’re eating a sandwich while, for me, it was a really big emotional experience. So balancing those emotions with talking to people about their jobs was tricky.

The big thing for me was that I don’t want anyone to be portrayed as evil in this story. The way we talk about Guantánamo is really reductive and dehumanizing—mostly of the prisoners who are there. But I think there’s also an impulse from people who don’t agree with Guantánamo to say, “The people who are working there are evil. The military is full of terrible people who do terrible things.” And, whatever I’m reporting on, I try to approach each person as a person. And talk to them like, “Where are you coming from? What experiences led you to this point? What sort of moral quandaries do you have?”

A lot of people join the military because they don’t have a lot of other options. They join the military because they need a job and there are no jobs. Because they want to go to college and they can’t pay for it. We’ve set up a system in our country where a lot of times the only option people feel like they have—if they want to survive and have a good life—is to join the military. I don’t think of that as, “Oh, those people are evil.” I think of that as, “What are the systems we’ve created that force people into this situation?” And then to not think or act in a way they think is morally right, but to “just do their job.”

That’s one big reason I wanted to have Matt Diaz in the book. He’s the only person I know of out of the thousands and thousands of people who have worked at Guantánamo who actually engaged in an act of civil disobedience. Who said, “I don’t agree with my job here, and I’m going to do what I think is right, even though it’s against the law.” I wanted to have his story in the book to say, “Okay, if you were in this situation—you as the reader—what would you do? Would you be one of the people who keeps their heads down and works for six months, gets paid, leaves, and then tries to forget about it? Or would you be someone like Matt Diaz, who tries to undermine the system to do what you think is constitutionally and morally correct and then pay a steep price for it?” I don’t think anyone who’s an observer, who’s a civilian like me, can stay on the sidelines and say, “Well, I would have done that differently.” Because we haven’t been in that situation. So I wanted to talk to people who were in that situation and say, “What was going through your mind? What were you feeling?”

Above, a page from Guantánamo Voices: the story of Moazzam Begg, illustrated by Omar Khouri.

Amberson: That section really points out how high the stakes were and how stressful that decision was. And also the eventual repercussions for that decision.

Mirk: Yeah, and at the same time I don’t want to let people who were in high-ranking positions there off the hook. Because every single person who works there says, “I’m just doing my job. The decisions on how the prison operates, or the fact that it exists, are all set in Washington.” By people who don’t have to face any accountability, who don’t have to face journalists asking them tough questions, or face the reality of the prison every day. It’s politicians and the George W. Bush administration who set this in motion, and it’s been politicians since then that have continued it.

I think a lot of people need to be held accountable in this situation. I don’t want to just shrug that off and just, “Well, you know, everyone’s got a moral conflict here.” Some people really have failed to do what’s right. And that comes down on the person at the very bottom of the pile in the military who’s a random person from Michigan who’s assigned to be a guard at the base whose life is traumatized from it.

Amberson: How did your perspective change during the course of the project?

Mirk: Well, I got a lot more comfortable talking about terrible things. I started off being more afraid to face this history. And the more I talked about it, the more I was like, “Look, we just have to be honest about what we did. And we have to be honest about what we continue to do.” That’s the only way to reckon with our past, and to try and make a better future. For me, that’s so applicable to every part of American life and American history. We really just want to say, “Yeah, yeah, some bad stuff happened in the past, but now we’re moving forward and it’s all good.” And that actually creates a lot of pain.

I’ve been thinking a lot about how we, as Americans, can face our past and reckon with it seriously. We have to make change, be accountable, and pursue justice if we want to have any chance at a better future. And I don’t know what that looks like in every case. It’s very complicated. But it’s something I’ve been thinking about a lot.

I’ve also been thinking about the ways Guantánamo has crept into the rest of our society. Like, this summer in Portland there have been these big protests and police and federal officers have been covering their badges, and that immediately reminded me of Guantánamo. The people who work at the prison—both guards and doctors who work there—cover their names because they don’t want to be held accountable. And I’ve also been thinking about how the stories we tell about people can really determine what happens to them. I think Guantánamo is a case of a group of people being thoroughly dehumanized in the stories the government told about them. And therefore, the rest of the United States hasn’t done anything about it. And I’m hoping that by changing the stories we tell, we can also change the place itself.

Sarah Mirk is a digital engagement producer for Reveal through the Center for Investigative Reporting. Since 2017, she has worked as an editor at The Nib, an online daily comics publication focused on political cartoons, graphic journalism, essays and memoirs about current affairs. She works with artists to create nonfiction comics on a variety of complex topics, from personal narratives about queer identities to examinations of overlooked history. Before that, Mirk was the online editor of national feminist media outlet Bitch, a podcast host and a local news reporter. She is also the author of several books, including Sex From Scratch, Open Earth, and Year of Zines. Mirk is based in Portland, Oregon.

Joshua James Amberson is a Portland, Oregon-based writer and creative writing instructor. He’s a regular contributor to The Portland Mercury and Hobart, and his work has appeared in The Rumpus, The Los Angeles Review of Books, and Tin House, among others. He’s the author of the chapbook Everyday Mythologies on Two Plum Press and is currently working on a book about eyes, vision, and blindness.