Captured

Who gets used in the quest to make art out of real life?

BY JOSHUA JAMES AMBERSON

WHEN I WAS in preschool, I woke up every morning, climbed onto a stool at the kitchen counter, and went to work with my watercolors and crayons like it was a job. From where there had previously been nothing—reams of white, perforated computer paper from my mom’s job at the Hewlett-Packard factory—I created something. I didn’t know where these images came from, didn’t even have a guess, I only knew I saw them. Otherworldly landscapes, abstract cities, my own constellation of superheroes. There were pictures inside of me, and when I came to the blank white, I pulled them out; I looked at the emptiness and saw what could be.

Like most rural boys, I soon fell under the spell of sports and spent my adolescence consumed by its questionable worth. When the spell broke in my teens, I found I still—at least internally—held on to the identity I had established as a preschooler. That kid with the obsessive drive and artistic vision was still me. I was convinced. It didn’t matter that my abilities were stuck at the level of a child—the identity held strong.

It’s difficult to be an artist when you have no skills in any artistic discipline. But I kept trying things out, hoping something would stick. When a darkroom photography class was offered my junior year of high school, I signed up. Like writing, photography was a thing most people were able to do that could also become an art. That possibility—the ordinary transforming into the extraordinary—attracted me. I didn’t know how exactly that transformation happened, but I wanted to find out.

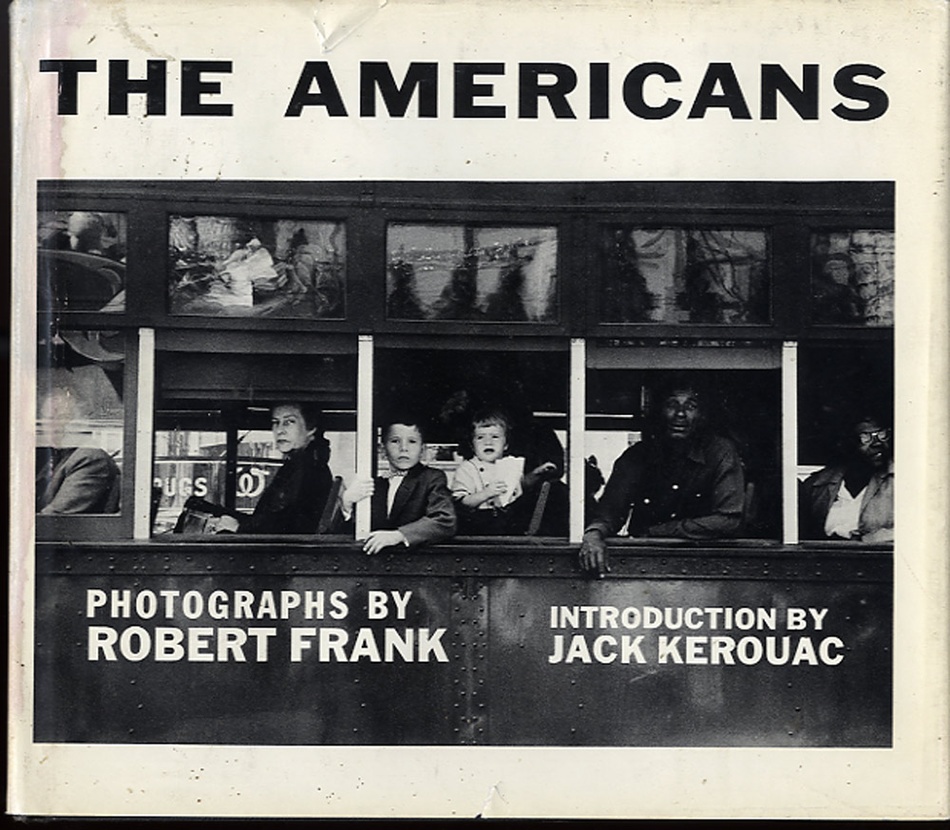

LIKE SO MANY young, aspiring photographers, I fell in love with Robert Frank’s 1958 book The Americans. Backed by a Guggenheim Fellowship, the Swedish-born Frank drove across the United States in the mid-fifties and, over the course of nine months, traveled ten thousand miles through thirty states, going through seven hundred and sixty-seven rolls of film and taking twenty-seven thousand photos. Those twenty-seven thousand were then whittled down to the eighty-three that became the book’s raw and perfectly baffling assortment of images.

I loved how Frank took cultural cues of Americana and turned them questionable and strange. A cowboy lighting a cigarette against a garbage can on a dirty city street. A grumpy diner waitress standing below a horrific image of Santa Claus and a sign for jumbo-size hot dogs. A woman in a window, her face obscured by an American flag. A vacant gas station in the desert with a large sign that says SAVE. Beyond the apparent commentary on American consumerism, American dichotomies and contradictions, I loved how the photos in The Americans caught people, again and again, with their masks off. The images were so unlike most photos I’d seen—forced smiles and awkward attempts at hiding awkwardness. Frank’s photos, I felt, were real. They revealed something hidden, in both the people and the country.

When I learned The Americans was part of a movement or style called street photography, I began making my way through the library’s photography section, trying to find more of it. Frank’s melancholic American road-trip photos led me to Walker Evans’s claustrophobic New York City subway photos, which led me to Garry Winogrand’s aggressive shots of New York City streets, which led me to André Kertész’s geometric studies of silhouetted figures on Parisian streets, which led me to Henri Cartier-Bresson’s streets the world over. I loved it all. This, I decided, was what I, one day, would do.

Photo by Garry Winogrand, New York, c. 1962.

MY LEAST FAVORITE English teacher doubled as the photography teacher. He liked talking about how, if we practiced hard enough, we could eventually work at the portrait studio in the mall. Even if I’d had a different teacher, there would have remained so many things I didn’t like about the class—crowding into the darkroom together, everyone watching over your shoulder, the way it required staying after school to get anything significant done.

But my biggest issues as a photographer occurred outside of the classroom and the darkroom. As a shy, overly polite teen, it was difficult for me to point a camera at someone’s face—even when my subject was aware of what I was doing and was willing. I’d imagined photography as a way to reveal my view of the world to the world, but I hadn’t thought about what that revelation entailed. It wasn’t as simple as it looked in Frank’s photos—the casualness and apparent ease was an illusion. So I often took pictures of coffee-mug handles and train rails, stacks of bricks, chair shadows. Even then I had to deal with other people. Each time I took a picture in public, there was someone asking what I was doing. I told myself that these people just couldn’t imagine the ordinary transformed, because I didn’t want to admit the obvious: taking a picture of a cup makes everyone look like a fool, regardless of their inner vision. It’s something I think about a lot now, watching others hover their phones over their brunch plates, while I judge. How can you judge? I ask myself. This was once, in a way, you. I try to convince myself it’s somehow different—I was after art while they’re after likes—but that’s just another story I tell myself.

FILMMAKER WIM WENDERS recently said he’s “in search of a new word for this new activity that looks so much like photography, but isn’t photography anymore.” In the age of latté roses, mirror selfies, and screenshots, I get what Wenders is saying: there is something different, something other about the current manner in which people visually document the world. It borrows aspects from art photography, advertising photography, photojournalism, and point-and-shoot casualness, while not quite being any of those things. But photography has always encompassed so many styles that Wenders’s statement also seems silly, snobbish. Photography has always resisted being any one thing, resisted being an art, resisted being something that can be universally held in high regard. Making any broad statement about photography is bound for failure, because photography is so much.

Photography is Sears portraits, gallery art, journalism, and porn. It’s a mountain range at sunrise, an abstract pattern on a body of water’s surface, a small rodent approaching extinction, a wool sweater on a handsome model. It’s bacteria on a petri dish, bodies at a crime scene, stars forming in the Eagle Nebula. It’s framed portraits on the mantle, old Life magazine special issues at the thrift store, dusty albums on the bookshelf, the head shots of aspiring actors, Instagram feeds, Facebook profiles, press photos. It’s weddings, graduation, and the first day of school. It’s disposable cameras, point-and-shoots, XLRs, Polaroids, medium and large formats, but mostly phones. It honors, it exploits, it educates, it turns us on and turns us off. “Photography evades us,” Roland Barthes writes. “We might say that photography is unclassifiable.”

AS A PHOTOGRAPHER, I took risks that rarely paid off. In community college, I did a photo series in twenty-four-hour grocery stores late at night, photographing my stoned friends examining fruit. I shot from the hip at checkout lines, parked myself at the automatic doors, tried to embrace the endless rows of overbearing fluorescents. If a project in the least ideal lighting conditions wasn’t enough, I decided to expose the images with transparency overlays where, in my childish scrawl, I scratched in lines of poetry I’d written. The result looked like an accident: barely legible words, existing without explanation, at the bottom of each print. I liked it, put a lot of thought and time into it, but to most people it was more or less unintelligible. I should have started with something simpler, something straightforward, but I couldn’t allow myself to be a beginner. I had too many ideas for that.

I did a photo series of my friend in his garage, hood up on his car, shop-light playing off the metal, contrasted against the surrounding darkness. I spent the entire photo session underneath, hidden, shooting up through the gaps between the block and the hoses. This is where I was most comfortable—with one other person, in a private location, the subject at ease, doing something he loved. Deep down, I didn’t want to pry or stare, didn’t want to make people uncomfortable. I wanted to soothe, to calm, to assist in helping another person lower their guard. But artists, in my mind, didn’t do this. This was the role of yearbook and wedding photographers—necessary roles, sure, but not imbued with the importance and romance of art. I tried to ignore the fact that my skills were likely more suited to the mall portrait studio than the art world. I tried to push myself out of my comfort zone, but every time I picked up a camera I questioned who I was.

Walker Evans in 1937, in a photograph by Edwin Locke.

DURING THESE YEARS, Walker Evans’s words were a mantra I prominently displayed in my journal: “Stare, pry, listen, eavesdrop. Die knowing something. You are not here long.” His words inspired me to be brave, to put myself out there without worrying about how others responded. But now, it’s hard for me to read his words without stumbling over the selfishness of them, the inherent privilege embedded within: knowing you can stare and get away with it, that you can pry without worrying—without having to worry—how it will make others feel.“There is an aggression implicit in every use of a camera,” Susan Sontag writes. It was this aggression that made me question myself each time I put the viewfinder to my eye, attempting to capture an image. I was not only taking a photo, I was shooting someone. But I didn’t want to capture, take, or shoot anything.

Among my friends, Hannah was the best photographer. She was forceful, brazen, confident—everything I wished I was. She didn’t worry about the silly concerns I obsessed over, didn’t overanalyze the verbs we use for photographing the world. She put herself and her camera out there. She brought it to every event and didn’t mind that it changed the air in the room, that it made people squirm. She was able to make art out of otherwise uneventful parties, knowing that everyone would be happy later, when the pictures were developed and the moment was in the past. She was sure everyone would forget how their bodies tensed, how the camera made conversation difficult, and would just remember the idealized moment within the photograph. And we did. Her photos gave us an instant nostalgia for events that, often, hadn’t been that great. Through her eyes, we wanted to live them again.

I wished I could accept the trade that Hannah made so easily: the moment for the artifact, the life lived for the art. But I was too aware of how the presence of a camera changed a room. But also: how the camera in my hands kept me from fully participating in life—that to put a camera to your eye is to observe rather than join.

I DID A PHOTO SERIES in an abandoned garden center. It sat on a semi-rural stretch of road, nothing nearby, and my friends and I liked to sneak in to dig through its wreckage. We always went late at night, beers in our backpacks, already tipsy, and climbed on the mountains of trash, avoiding broken glass, breaking more in the process. During these trips I became fascinated with the accumulation, the mass of stuff. Nothing had been packed and hauled off when it closed years before, it was all just clumsily fenced and left for the weeds to cover, for the punk kids to break down the remaining pieces of its existence.

Going during the day was a different experience. Not as charged with mystery—it was just a lonely place filled with a dream that didn’t work out, the end of so many livelihoods. I didn’t know how to capture it all. The sheer amount of stuff was perfect for late-night explorers, but it was overwhelming when peering through the camera’s tiny frame in the late afternoon. I brought friends with me and had them wander around and give some humanity to all the objects. Still, I didn’t know what to focus on. There was just so much.

Though I tried to pretend my photo series were documenting real events and places—the world of grocery stores in the middle of the night, a friend at work in his garage, an abandoned garden center—my main subjects for these were essentially models. They were manufactured, inorganic, placed. They wouldn’t have been there without me asking them to be there, and it showed. When I studied other photographs, I saw this falseness. A common pose was acting casually. Pretend like you’re not in front of a camera, I heard the photographer instructing. It tainted so many otherwise wonderful photographs: the act. The only way around it, I felt, was to sneak shots, not letting your subject know they were a subject. Be like the street photographers, I told myself. Be daring and clever, stop caring. But I couldn’t.

GOOGLE “STREET PHOTOGRAPHERS” and you’ll notice a common thread: regardless of which sections of the population they’re known for photographing, they’re almost uniformly white. And largely men. In the top ten search results, there are only two women and one—Vivian Maier—has only become known in the past decade, years after her death. In the top forty results, there are only three people of color.

It’s the privilege of being able to look. And even though I couldn’t place it at the time, this was part of my discomfort. In my attempts to be a photographer, I was asserting my privilege as a young white man in a way that was loud and undeniable, decidedly different than how I went through the world—cautious, afraid of being an annoyance or an upsetting presence—and I didn’t like how it felt.

Having read biographies and watched documentaries about my favorite street photographers, I know that most, while considering themselves artists first and foremost, also saw their work as a way to spread empathy—to ask viewers to consider the humanity in people very different than themselves. Most seem like they were in part guided by Lewis Hine’s turn-of-the-century idea of “social photography,” where, according to historian Alan Trachtenberg, “a picture was a piece of evidence, a record of social injustice, but also of individual human beings surviving with dignity in intolerable conditions.” From their perspective, they were using their privilege for good.

But they were also well aware of the discomfort they caused, of their own forcefulness. Frank perhaps put it most succinctly when he said that, as a street photographer, “you intrude.” Cartier-Bresson, a self-proclaimed humanist, described his technique as a street photographer using the words prowl, pounce, trap, and seize. These words may not be terribly offensive, are perhaps used playfully, but they certainly emphasize the moral ambiguity. While their pictures still seem more surprising, more emotionally open than almost any other photographs I know of, I wonder: What about the people in the photographs? Was it an honor for them? Or a burden?

Having taken a lot of photographs of people, I know that the subject mostly sees their self in the end product. And, of course, it’s difficult to look objectively at a photo of yourself. You look past the frame, the lighting—really, the composition as a whole—and you go straight to your face. You see your open pores, your mussed hair, your double chin, the lines around your mouth. It’s not art, it’s you.

WHEN I SET MY camera down, I remembered how to be present in the moment. I stopped feeling guilt for taking a photo, guilt for not taking a photo. I stopped thinking about what life would look like later, when it was printed out and hung on a wall, but what it felt like right then. I stopped worrying about what I wasn’t capturing on film and remembered what it was like to just experience. I was twenty-two years old and very concerned about experience. I didn’t want to miss anything. Capturing one moment, I realized, meant missing so many others.

I took a walk in the woods with a friend and instead of mentally framing a shot that he was in, I saw him. I noticed his shy eyes, his mind searching for something bigger he didn’t yet have words for, the depth of his intelligence—aspects of him I had previously missed. If anything, I learned more from quitting photography than from practicing it.

THE WELL-KNOWN street photographers of today tend to be more respectful. They’re in large part fashion photographers, or casual sociologists, and we typically know them by their photo blog or Instagram project—Humans of New York, Fruits, The Sartorialist. And while I appreciate this work and enjoy it, these photographers are sharing a concept more than a particular artistic vision. These photos are missing what initially attracted me to Frank or Evans, what I love about Maier, with her secretive box camera, held at the stomach instead of to the eye: seeing people with their guards down. My well of empathy is deeper because of The Americans, because of Cartier-Bresson and Evans and Maier. But does that make the photos ethical?

In the majority of today’s popular street photography, people pose. And there’s power in the well-posed photo. I love when I can see that brief relationship between the subject and the photographer, or simply the relationship between the subject and the camera’s lens. Posed photos carry both the idea of self that the subject wants to project and the self the subject can’t hide. But they don’t move me like a candid photo—photos where the subject is open, messy, full of life. “Once somebody’s aware of the camera, it becomes a different picture,” Frank said. “People change.” When I look at popular street photography today, I see people with their masks on. I see how something is lost in the respect.

In this era, where so much is being documented and everyone’s a street photographer with their own gallery wall and audience, I often wonder about the lines between privacy and documentation, respect and art. I still want to see people photographed with their guards down, their masks off, showing me the vulnerability I believe we all share and carry within us, but that most of us look past when we walk the streets. But I don’t know if I believe the world is up for grabs, that people in public are available subjects simply because they’re in public.

Ultimately, I still ask the same questions I did when taking photos, a decade-and-a-half later, as a writer: What’s off limits? Who gets used in my quest to make art out of real life? Is what I do ethical? I often write about my family—private people, living private lives—without letting them vet what I say, or how they’re portrayed. I write about my intimate relationships with my friends, with former lovers, I write about students and people I meet at parties and strangers I see on the bus. Several times, I’ve written extensively about the private lives of the dead, simply because they were people who, at some point in their lives, made art for public consumption. Is any of this right?

Maybe I think about it more because my family lives rurally and values privacy so much. To friends who grew up in cities or suburbs, who had neighbors they could see from their windows, these questions may be a little less ambiguous. My mom and my step-dad often talk about how important it is to be left alone. They live miles from town because they don’t want people around watching what they do—even though most of what they do is work in the yard, hang out with their cats, and watch TV. It doesn’t matter that their activities aren’t scandalous or illegal, they just want to be left alone.

Privacy is a way we maintain our identities, and the masks we wear in public are just an extension of that, a similar act of self-protection. But when faced with our human inclination to look, to wonder, and create, we come to art’s general moral ambiguity. Most of us want our lives private, and the nonfiction art we consume, raw and revealing. Excavate, interrogate, be vulnerable, we say in nonfiction writing workshops. Take the mask off. It’s your story, we say. But, of course, it’s never just your story. And here we are again: that ambiguity. A picture; a story; a life, captured.

Joshua James Amberson is a Portland, Oregon-based writer and creative writing instructor. He’s a regular contributor to The Portland Mercury, Hobart, and Fiction Advocate, and his work has appeared in The Rumpus, The Los Angeles Review of Books, and Tin House, among others. He’s the author of the chapbook Everyday Mythologies on Two Plum Press and is currently working on a book about eyes, vision, and blindness.